Richard Jackson: Ain’t Painting a Pain

On February 17, 2013, the Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA) presents one of the most ambitious exhibitions ever organized by the museum. Richard Jackson: Ain’t Painting a Pain is the first retrospective devoted to one of the most radical artists of the last 40 years. Jackson (b. 1939 in Sacramento, CA) has expanded the possibilities of painting more than any other contemporary figure and his wildly inventive, exuberant, and irreverent take on "action" painting has dramatically extended its performative and spatial dimensions, merged it with sculpture, and repositioned it as an art of everyday experience rather than one of heroic myth. The only American presentation of Ain’t Painting a Pain is on view in Newport Beach from February 17 through May 5, 2013. The exhibition then travels to the Museum Villa Stuck in Munich, Germany and to the Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art (S.M.A.K) in Ghent, Belgium.

The exhibition is conceived as a series of eleven room-scale installations from 1970 to 2011, most never before shown in the United States, accompanied by over 150 of Jackson’s related preparatory drawings, works on paper, and models. Foremost among these is 100 Drawings (1978), each a different proposal for a painting project, presented for the first time since its creation. To especially mark the occasion of this retrospective, Jackson will produce a major new outdoor piece, Bad Dog (2013), a 28 foot-high puppy establishing his territory on the side of the museum. The exhibition, curated by OCMA Director Dennis Szakacs, is the first devoted to a living artist to occupy the museum’s entire exhibition space.

"Jackson’s humility and humor make his work all the more bold, and his example of quiet perseverance devoted to difficult, uncompromising work is one that other artists, and all museums, would do well to follow more frequently" states Szakacs.

Jackson’s Early Years (1969-1988)

Based in Los Angeles since the late 1960s, Jackson exhibited at the legendary Eugenia Butler Gallery with artists such as Bas Jan Ader, John Baldessari, Ger van Elk, Edward Kienholz, William Leavitt, and Allan Ruppersberg. Jackson’s work was entirely site-specific—each piece was created within a museum or gallery space and destroyed at the conclusion of the exhibition. Ain’t Painting a Pain includes recreations from the three main series that he developed over the first twenty years of his career: large-scale “wall paintings”; room-size “painted environments” that viewers could enter; and monumental “stacked paintings.” More than simply innovative formal experiments, these works helped set the tone for much of the most important art to emerge from Los Angeles over the next three decades, where unfettered ambition and irreverence toward cultural orthodoxies combined to unleash brash new forms.

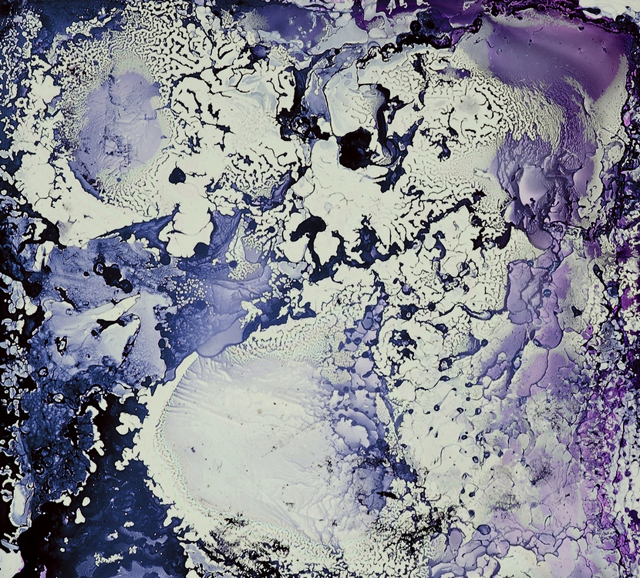

Much of Jackson's work during the 1970s and 1980s introduced a series of inventive inversions and concealments aimed at upending the technical and stylistic conventions of painting, while still reveling in the material qualities of paint. Jackson’s interest in the uncontrolled application of paint may be linked to Kienholz’s “broom paintings” of the 1950s, and his delight in thick, gloppy surfaces is related to Wayne Thiebaud’s paintings, especially the glossy serial images of deserts, cakes, and cookies. Both artists were early and important influences on Jackson.

With Untitled (Maze for Eugenia Butler Gallery),1970, one of the Jackson’s most essential works, he began to reconfigure the viewer’s perception of canvas, paint, space, and even time. The installation is a 20’ x 20’ enclosure with 9’ high walls made from stretched canvas, that are “painted” by sliding another wet canvas through the corridor of the maze. In this work, a “painting” is transformed from illusionistic space into architectural space, may be viewed only in parts (rather than as whole), and is experienced one way upon entering and another upon exiting. Recreated for the OCMA exhibition, Untitled (Maze for Eugenia Butler Gallery),1970, set the stage for an astonishing series of painting projects unprecedented in the history of American art.

Ain’t Painting a Pain also includes new site-specific Wall Paintings at OCMA and at each museum on the exhibition tour. The Wall Paintings are created by sliding wet canvases across gallery walls to create abstract murals of impressive graphic power and formal variety (past works have reached 13' high by 79' long). Here, the backs of paintings become as important as the fronts, one painting is destroyed to make another, and canvas is transformed from a surface to receive paint into a device for applying it.

Jackson began his Stacked Paintings in 1980. In this series thousands of stretched canvases are painted and stacked facedown to create monumental enclosures and sculptural works. Paint becomes a means of adhesion as much as one of expression, and the act of “painting” is reduced to one idea repeated over and over again, Jackson’s critique of the stylistic conventions that he believes are pre-ordained in the medium. 5050 Stacked Paintings is a work conceived in 1980 that will be built for the first time especially for Ain’t Painting a Pain. The installation of 5,050 paintings measures 30’ long x 15’ wide x 10’ high and will be by far the largest stacked work ever produced by Jackson.

The exhibition features an extensive selection of preparatory drawings for painted environments, wall paintings, and stacked paintings, all of which show Jackson’s meticulous planning process, exquisite draftsmanship, and the extraordinary amount of labor that the artist invests in these large-scale works that are ultimately destroyed and live on only in viewer’s minds. In 1988, Walter Hopps organized Jackson’s first and only survey at the Menil Collection in Houston, an exhibition which ultimately led Jackson to recognize that he had perfected his means of production and exhausted his ability to push the concepts of these series any further. Commenting on the work of this period, Jackson stated:

"...the more I did them, the more familiar I became with the materials, the nicer they came out. That's why I lost interest in them. When you take part in an activity or are involved in a process, something can go wrong, and that's when it gets interesting. It's not interesting if everything is going well."

Richard Jackson, Big Ideas-1000 Pictures, 1980/2011

Jackson’s New Directions (1992–present)

By the early 1990s, Jackson began to build all manner of elaborate “painting machines,” which he activates prior to an exhibition opening, and which viewers experience as evidence of a performance rather than as a performance itself. A startling break from the conceptual abstraction that had defined the first half of his career, Jackson began moving toward a conceptual realism that employed the figure to investigate the problems of picture making, moving from an essentially deconstructive approach to one that was more generative and was about remaking rather than disassembling. These mechanized works employ pumps, motors, fans, propellers, air compressors, and spray hoses to deploy paint in increasingly inventive and outlandish ways. Ain’t Painting a Pain includes seven of these room-scale works created over a twenty-year period, six of them Jacksonian reinterpretations of canonical works by Jacques-Louis David, Edgar Degas, Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Seurat. In foregrounding this particular series—one of the most sustained and rigorous investigations of art history in all of contemporary art—the retrospective seeks to establish the framework for Jackson’s ongoing struggle with painting’s past and future.

With La Grande Jatte (after Georges Seurat), for example, the artist recreates the 1886–86 pointillist masterpiece by dipping pellets into paint and firing them from a pellet gun at the canvas. Jackson began the project in 1992 and after approximately 90,000 shots the work is barely 10% completed. No matter how much labor Jackson applies to its production, the painting will never be completed, upping the ante on Seurat’s labor intensive painting technique, and establishing the sly and subversive attitude that Jackson would bring to his interpretation of art historical icons.

Jackson's Painting with Two Balls (1997) co- opts Johns’ famous 1960 critique of abstract expressionism to make a massive “action” painting by using a Ford Pinto to power two large spinning balls that throw paint in all directions into a large room. The Laundry Room (Death of Marat), 2009, transforms David’s 1793 pieta of the French Revolution into a three- dimensional, life-size mis-en-scene that viewers may enter. Jackson’s update links the extremism of the French Reign of Terror to the American war on terror, and the highly polarized political debate that defines both periods. Like The Laundry Room, Jackson’s The Blue Room (2011) also turns a painting into a sculpture that makes a painting; in this case using Picasso’s 1901 The Blue Room (The Tub) for inspiration. Jackson inserts Picasso’s rival, Marcel Duchamp, into the scene by replacing Picasso’s girlfriend Blanche from the original painting with a sculpture of the nude Eve Babitz taken from the well-known photograph of her playing chess with Duchamp during his 1963 retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum.

During this period Jackson also produced several autobiographical works and Ain’t Painting a Pain includes two major room-scale examples: Deer Beer (1998), which combines Jackson’s passion for hunting, art history, and painting; and 1000 Clocks (1987– 1992), which was made to mark the artist’s 50th birthday and has not been shown in the United States since its premier in Helter Skelter at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 1992.

For much of the 1990s through the present, Jackson was exhibited far more frequently in Europe than in the United States. His relationship to Bruce Nauman and Paul McCarthy, who were both embraced there long before achieving renown here, helped introduce Jackson’s work to curators more open to its exuberance and iconoclasism. Jackson’s rethinking of the forms and structures of painting also found a far warmer reception in Europe, which arguably has a deeper tradition of artists who up-end its conventions while still embracing the activity (Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, Niki de Saint Phalle, Daniel Spoerri, and Gunther Uecker among many others). While teaching at UCLA in the early 1990s, Jackson was also an influential mentor to Jason Rhoades and to a new generation of artists who emerged from Los Angeles.

In the United States, Jackson is the heir to Pollock, Rauschenberg, and Johns. Their breakthroughs, however, took successive generations of American artists away from the further expansion of painting and toward the new genres that their work anticipated, which left Jackson outside of the prevailing narratives of post-1960s American art. Ain’t Painting a Pain offers a full-scale reassessment and continues the museum’s longstanding commitment to championing essential yet under-recognized late career artists.

The exhibition runs from Feb 17, 2013 to May 5, 2013. For more information visit the OCMA official website. Richard Jackson: Ain’t Painting a Pain is made possible by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Jean and Tim Weiss, Rennie Collection, Vancouver, and Hauser & Wirth.

.png)